You’re Hunter Wilder, a 41-year-old guidance consultant at Fidelity Investments, who leaped out of your comfort zone to try something bold. You took on a major company with 6,000 employees to prove a point about customer service.

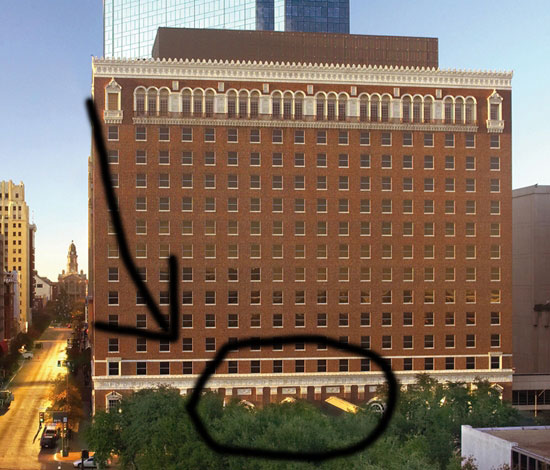

This week, you stood by yourself in a quaint courtroom in the old 1895 Tarrant County Courthouse in Texas and did your part for every customer who ever felt wronged.

You sued Towne Park, the company that handles valet parking at the Hilton Fort Worth, across from the Fort Worth Convention Center.

Your car was stolen last year when you were fetching it from the parking attendant. A thief ran up to the running car, jumped in and drove away. The valet company’s insurance company wouldn’t pay, so you sued in small claims court.

You asked for a jury trial and ultimately ended up seeking $3,000 to cover your expenses. Your quest took up three hours of court time for you, your two witnesses, the justice of the peace, his bailiff, six jurors, the Towne Park executive who watched, and Towne Park’s hired lawyer.

But actually, nobody seemed to mind.

On paper, you sued for the $1,000 insurance deductible you paid after your 13-year-old car was recovered and needed repairs, a $1,000 lost laptop, a $350 briefcase, a $225 radar detector, a $150 GPS device and court costs. But really you say you sued for more than money.

“I just want the jury to say I was right,” you say. “I want Towne Park to know they were wrong.”

You’re Hunter Wilder, a man who admits that he never watches lawyer shows on television. You couldn’t even pretend to know how to defend yourself. You apologized to the jury for your stumbling. The judge kept correcting you. The other lawyer? He outwitted you, almost.

Your claim was originally denied by the insurance company because Towne Park had reported that the valet was assaulted and pushed down. The car, you were later told, was taken by force. Not quite, you said. But when you tried to bring up the insurance company’s rejection, the judge told the jury to disregard your comments. Nobody entered evidence of an assault. So much for that.

You wanted to be so sure that everyone would know how it happened that you built a diorama with details so precise the folks at The Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas would be wowed. Even your judge, Precinct 1 Justice of the Peace Ralph Swearingen, was impressed. How could he not be? You went back to the hotel and took measurements.

“It’s to scale except for the bricks,” you told him.

“Is the car appropriate to scale, too?” the judge asked. “Looks like a Ford Mustang.”

“It’s a coupe,” you explained. “I couldn’t find a sedan. But the colors are appropriate.”

The model showed the car, the thief, the valet attendant and two witnesses.

The lawyer for Towne Park tried to show that you were distracted by a guitar-playing street minstrel that night, but you didn’t fall for that. Heck, the minstrel didn’t even make it into your diorama.

You testified, asked questions, made your arguments.

The lawyer, from Richardson, flashed a Texas Supreme Court case he dug up to thwart your case. It came down to this: How can a valet attendant be responsible when a criminal does the deed?

Your response: Fort Worth has an ordinance against leaving a parked car running when it is unattended. You tried to show that the key should have been removed or the attendant should have stayed at the car, instead of leaving it with the door wide open.

The scene of the crime: The front of the Fort Worth Hilton is known as the last place where President Kennedy made his last public speech on Nov. 22, 1963.

You may not be a lawyer, but you knew how to talk to the jury. In your closing statement you explained it in a common-sense way: “It would have been as simple as taking the key out of the car. They created the condition.”

The jury deliberated 15 minutes. One juror, lawyer John Sutton of Fort Worth, said later that the six jurors went around the table, and everybody came to a quick consensus. “Would you walk away from a car with the motor running and a door open?” Sutton asked.

The verdict was announced. Towne Park owes you $3,000. A juror winked at you as you left the courtroom.

You’re Hunter Wilder, a fellow from Azle, Texas who showed how standing up for yourself is never a lost cause. You’re no lawyer, for sure, but if you’re half as good a guidance consultant as you are at building dioramas and defending yourself, you’re all right.

# # #

Read a previous Watchdog Nation report about this case here.

# # #

Dave Lieber, The Watchdog columnist for The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, is the founder of Watchdog Nation. The new 2010 edition of his book, Dave Lieber’s Watchdog Nation: Bite Back When Businesses and Scammers Do You Wrong, is out. Revised and expanded, the book won two national book awards in 2009 for social change. Twitter @DaveLieber